Danny Morrison’s "Rudi - In the shadow of Knulp" - A Review

Fellow writer Danny Morrison

In the early 2000s several journalists tried to convince me that Danny Morrison, Sinn Féin’s former director of publicity, was in fact the infamous – cue drumroll and da da da daaah music - Stakeknife.

Stakeknife was supposed to have been the British spy at the heart of the IRA – with the back story that Mr Knife guided one of the most successful guerilla movements that has ever existed into a dead end of pacification and normalisation. Danny Morrison, in fact the whole of the "Adams clique" in Belfast, was accused of effectively (and secretly) working towards a ceasefire situation agreed with section of the British establishment whilst the republican movement as a whole was out risking its collective neck for the cause.

One single fact exposes this raiméis for what it is. In the very period when this alleged Adams clique was supposedly in league with the British, the British were busy trying to kill them – all of them. Every man and woman jack of them. Gerry Adams, Morrison himself, Joe Austin, Pat McGeown, Alex Maskey, Martin McGuinness all of them. Indeed two of the brightest flames in what would become the Sinn Féin renaissance (Maireád Farrell and Sheena Campbell) were brutally snuffed out before they could go on to lead that party as women and republican socialists.

Now why do I mention this at the start of my review of Danny’s excellent novel - "Rudi - In the shadow of Knulp"? I do so because Danny is a decent man, a beautiful writer and lifelong republican who has suffered the triple indignity of seeing his comrades die (including his close friend IRA volunteer Caoimhín Mac Brádaigh shot when unarmed and confronting British asset Michael Stone at Milltown); himself missing assassination by inches (he on one side of a wall, a death squad on the other), and then having his name and that of his comrades sullied and vilified because of a very clever British psyops campaign which a surprising number of people, not to mention journalists, fell for.

The British have played this post colonial tactic in every country they have ever governed - leaving behind booby traps of doubt and limpet mines of dubious assertion in the hope that the “natives” would detonate each other. It is nothing personal, merely second nature to them as rulers. A Machiavellian culture honed over hundreds of years. We, meanwhile, are the more their dancing fools for not learning this lesson.

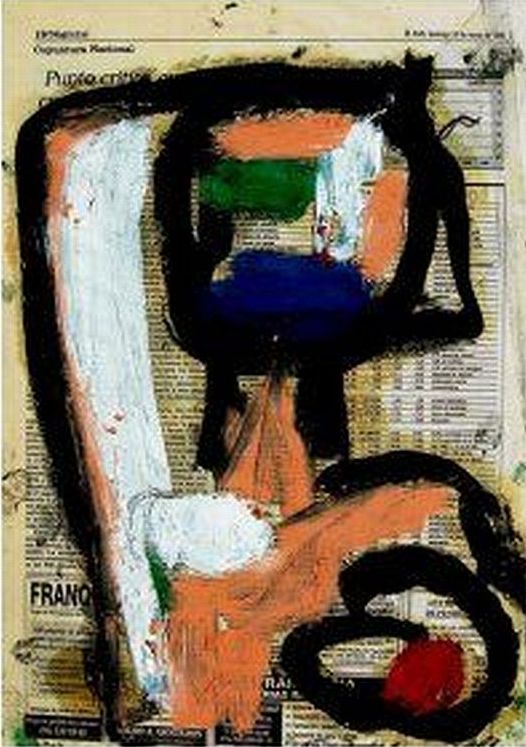

Rudi - In the shadow of Knulp, Danny Morrison

Of course it can be gleaned from the above that Danny Morrison and I are good friends and where any review of his literary output is concerned I freely admit the danger of partiality. However, true friends do not brown nose each other and any bias I may have is balanced by the fact that I want to push this friend to further literary heights. Knulp does not reach those heights but is a poignant and engaging step in the right direction.

Danny’s abiding interest in the German author Hermann Hesse forms the background to the title of his book- "Rudi - In the shadow of Knulp". Hermann Hesse’s truly brilliant novel Knulp was published in 1915 (so in the middle of the first world war) and features a vagabond or inveterate drifter – the eponymous Knulp. There is not space here to describe this uplifting and moving novel but there is a very good Wikipedia summary of Knulp here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knulp

However, suffice to say that Hesse’s meditations on man’s search for individual authenticity, autonomy and some kind of transcendence – the sense that we are more than the sum of our physical and rational parts – are key elements of Hesse's Knulp, where the hero plays a kind of Pied Piper role with his mouth organ, songs and poetry, his charming ways and gallantries. Knulp is popular wherever he goes but can never settle. In the end, in a dialogue with God, or we might say his greater self, he learns that his call in life was to engage and entertain people – or as Danny Morrison puts it in his own novel – he “left a charm” in every home.

Morrison’s Rudi (a Protestant who comes of age in post second world war “Northern Ireland" in a town that might be Banbridge) leads a life very similar to Knulp, but Rudi’s journey as a drifter takes him from the North to Cork and back again. Rudi’s two key relationships in the book are both with women – teacher's son Rudi falls in love with a woman called Isabel who in modern parlance would be a babe but also turns out to be fickle and disappoints him. From this point, Rudi goes downhill and begins his life as a drifter. He drops out if you like and eventually ends up in Cork where he is befriended by a couple who have a young daughter called Rebecca.

Apart from one issue, which I shall explain shortly, Danny’s description of the interactions between Rudi and these Cork people (as well as Rudi’s brilliantly depicted friendship with girlfriend Isabel’s brother Laurence) represents some of the best writing in the book and makes it a worthwhile addition to anyone’s library. There is also an abiding tension in the book because of the murder that happens at the start of the narrative and sounds a background note as events unfold.

Danny Morrison's All The Dead Voices - a stunning set of essays

Danny Morrison is always at his best when he describes exchanges between people, their dialogue, the decisions they make in particular situations, especially in moments of crisis or tension. His book All The Dead Voices brings all these talents to the fore and in my view (along with his jail journal – Then The Walls Came Down establishes him as one of Ireland’s foremost essayists. The problem with Danny Morrison the novelist is that he does not quite reach that level of “high seriousness”. Not yet.

What I mean by this is that in Herman Hesse’s Knulp (which by definition must be the benchmark for this novel), we are never in any doubt that we in the presence of a writer who is wrestling with the deepest questions of life, even in its most apparently frivolous moments. The vagabond Knulp has a sombreness, a Gravitas, that Rudi lacks.

I’ve spent about a month pondering this question of the slight lack of nobility that Rudi displays and believe that this stems from two things: a) Danny Morrison shrinks back from making judgements about his characters, or allowing them to do the same and b) that Rudi suffers slightly in the editing.

Herman Hesse’s Knulp lives a life as a wild rover because the character Knulp took a decision to take the road and depend on people’s charity and empathy (two values described with verve and deep pathos in both books). However, Danny’s Rudi is seemingly forced into this life through a bad reaction to an albeit emotion laden but everyday event.

In an Irish context, the best comparison when making this point about high seriousness when considering vagabond books is to stand Rudi next to Seosamh Mac Grianna’s Mo Bhealach Féin, which, whilst not without humour, is an acerbic and severe account of the writer’s roving and his disillusion with post 1916 forces in Ireland who usurped the Gaelic ideal. Mac Grianna struggled with huge ideas and was not wary about stating a position. Danny Morrison has the creative wherewithal to reach Mac Grianna’s level of intensity and forensic psychological examination (Mac Grianna wrote his own novels, translations and literature in Irish). The same goes for his clear aspiration to emualte Hermann Hesse but you feel that he has yet to release the utter core of his creative self.

Rudi the book also suffers because (according to my knowledge of the Protestant community in rural areas of the North) not enough attention was paid to how their outlook and traditions affects governs their lives. For example, unless I blinked and missed it, there is no explanation as to why Rudi has that name, when this would have been an issue for him growing up. Also, it was always and still is a big thing for Protestants to move South, yet this is never adressed. Nor do I believe that such a community would use expressions like – “what are you like?”, or the ubiquitous Belfast “OK”, which is tagged onto the end of a sentence to reinforce an emotion – "it was a good speech OK", "I liked it OK", "he’s a good player OK" etc. The same linguistic quibble applies to the people of Cork.

A keen eyed editor might also have spotted a crucial device that Danny uses in the book but throws away. For there are tiny moments where Rudi talks to himself and this would have been a perfect vehicle for Rudi’s deeper pondering on life. The alternative was to use Laurence in this role as sounding board; instead we have to rely on the unequal and somewhat reticent relationship between Rudi and the much younger Rebecca who gets our hero to open up about his love for Isabel. As it is, in my opinion, we are never brought fully into Rudi’s psychological and emotional world, his worrying about life and poetry or the lack of it, in the way we are with Knulp in Hermann Hesse’s masterpiece.

All the above said, I will leave readers with a moment where Danny does indeed reach a level of high seriousness and we get a hint of the political and philosophical drive that underpins Rudi’s need to be a poet. Buy it. You will enjoy it.

Her house, a whitewashed cottage with mullioned windows, one

gable shingled in ivy, overlooked the sea. She had a lot to preoccupy her, but occasionally she would remember Rudi, though it had been many years since she had seen him. She wondered what he would think of the success she had made of herself, the splendid home she lived in.

"Time and the world, money and power belong to the small people and the shallow people," he had quoted to her one day.

What had become of him? Would, after all this time, anyone in Lisliath or Drumbridge know?

Where are you going to, you would ask him. "Off to Rome to see the Pope," he would reply. She smiled at him making up often quite simple poems as they walked, or his improvising something on his mouth organ to please her, chords that could bc expressively sweet and implicitly sad.

She called her dog for their usual morning walk along the cliff. A Cocker Spaniel sidled up to her, panting with excitement. She rubbed its thick curly ears. "Lets go, Columbus!" she said.

@Paul Larkin

Carrick, Gaoth Dobhair,

Mi an Mheithimh 2013